"Bhaiya, twenty bucks I'll Paytm you, batana if I need to send more" - this is something I have heard all my friends say at least once. I grew up in Gurgaon, experiencing what many would consider a privileged upbringing. In that sphere of society, English was omnipresent. I attended an English-medium school where teachers would scold us for speaking Hindi. At home, my parents beamed with pride when I could read English signs outside our house. They would give me Geronimo and other English novels, praising my ability to skim through them effortlessly.

I distinctly remember a time when I felt extremely proud that I managed to read an entire chapter of a book during my English class out loud without hesitation. I also distinctly remember indifference when I couldn't do the same in my Hindi class. Every subject - from mathematics to history, physics, and even Sanskrit literature - was taught in English. Our mother tongue was relegated to a 45-minute period at day's end, after lunch when food coma peaked and our minds were already counting down to 4 PM, eager to head home.

Indians love English. It's regarded as the language of the literate, of a more civilized age. People who speak fluent English (or better yet, with an accent) are traditionally viewed as smarter, more intelligent, and generally more well-read - even more attractive. Drive through any Tier-1 or Tier-2 Indian city today, and you'll see English translations on every billboard, direction board, and hoarding. This isn't mere convenience - it's expectation. While you might think these translations are just a metropolitan quirk, you'd be wrong. Even in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, English vernacular dominates the streets.

According to the Indian census 2011, about 10.2 percent of the Indian population speaks English, whether as a first, second or third language. And according to the same survey, English proficiency is heavily linked to education level and social class. Under the Indian social classification system, upper-caste Indians were three times more likely to speak English compared to Indians who belonged to scheduled castes or scheduled tribes, which make up 25% of the population. For perspective, only 3 percent of rural respondents to the survey reported that they could converse in English.

This education-social class-opportunity trinity shows a clear pattern: as education levels rise, individuals increasingly accept English as both norm and aspiration. But that doesn't stop the remaining 90 percent of the country fawning over the colonial language. Punjab alone hosts hundreds of IELTS and TOEFL training centers, preparing young people for English proficiency exams - their ticket to Western nations, particularly Canada. In Delhi NCR, parents wage fierce battles for private school admissions. Why? The answer is simple: private schools offer English as the primary medium of instruction, while government schools teach in vernacular languages.

Children aged 2-4 undergo multiple rounds of interviews - yes, rounds - for kindergarten admission at private English-medium or Christian Convent Schools, especially in Delhi NCR. I remember my own experience interviewing for The Shri Ram School in middle school: a three-hour examinations covering English, mathematics, and physics, followed by an interview with the principal who assessed my personality, behavior, and most importantly my fluency in English. Take Sandeep Arora, a Gurgaon resident I spoke with. His story of securing his son's admission to one of Gurgaon's premier private schools seems almost surreal. Lines to apply for kids start forming in front of these schools at 5 AM during admission season, he told me. I got there at 4 AM. Luckily, we were among the first ones in, so we got an interview.

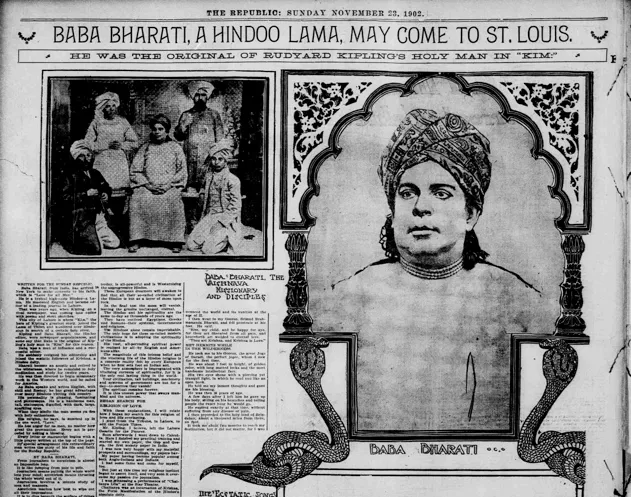

This linguistic hierarchy wasn't accidental - it was engineered nearly two centuries ago. In 1835, Thomas Babington Macaulay, President of the General Committee of Public Instruction, delivered his infamous Minute on Indian Education. This document would reshape India's educational landscape in ways that reverberate today. What's often forgotten is that pre-colonial India had a sophisticated educational ecosystem. Centers of learning like Nalanda and Takshashila were renowned worldwide. Sanskrit served as languages of scholarly discourse, while regional languages flourished in literature and daily life. Historical records suggest literacy rates in many parts of pre-colonial India actually exceeded those of contemporary Britain.

Here's an infamous Macaulay quote for you: “It is scarcely possible to calculate the benefits which we might derive from the diffusion of European civilisation among the vast population of the East. It would be, on the most selfish view of the case, far better for us that the people of India were well governed and independent of us, than ill governed and subject to us; that they were ruled by their own kings, but wearing our broadcloth, and working with our cutlery, than that they were performing their salams to English collectors and English magistrates, but were too ignorant to value, or too poor to buy, English manufactures. To trade with civilised men is infinitely more profitable than to govern savages. That would, indeed, be a doting wisdom, which, in order that India might remain a dependency, would make it a useless and costly dependency, which would keep a hundred millions of men from being our customers in order that they might continue to be our slaves”

His goal was explicit - to create what he called a class of persons Indian in blood and color, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. This wasn't just cultural arrogance; it was calculated policy.

In another part of his monologue, Macaulay describes what he calls – “the proudest day in English History”. Macaulay states, “that by good government we may educate our subjects into a capacity for better government; that, having become instructed in European knowledge, they may, in some future age, demand European institutions.”. Things begin to get clearer now. The enablement of Indians with English instruction under the guise of “civilizing the native population”, was a clear directive aimed at introducing a false sense of desire of English culture, tradition and life. For Macaulay understood that no other Empire such as the Mughals nor the Turks previously had. An Empire based on persecution, violence and terror cannot last, as brick, stone and steel are temporary, fickle, and fragile. However, ideology is “exempt from all natural causes of decay”. Violent invaders made Kings and Rulers who were capable of defending their home and society from aggression, however the British mentally incapacitated the people completely.

"That by good government we may educate our subjects into a capacity for better government; that, having become instructed in European knowledge, they may, in some future age, demand European institutions. Whether such a day will ever come I know not. But never will I attempt to avert or to retard it. Whenever it comes, it will be the proudest day in English history. To have found a great people sunk in the lowest depths of slavery and superstition, to have so ruled them as to have made them desirous and capable of all the privileges of citizens, would indeed be a title to glory all our own [...] There is an empire exempt from all natural causes of decay. Those triumphs are the pacific triumphs of reason over barbarism; that empire is the imperishable empire of our arts and our morals, our literature and our laws" - Thomas Babington Macaulay, 17 June 1833.

The irony of our linguistic inheritance runs deeper still. While we pride ourselves on being a sovereign nation that threw off colonial shackles, we continue to measure success through the very yardstick our former rulers left behind. In boardrooms across Mumbai and Bengaluru, presentations flow in English while regional languages are reserved for chai breaks. Job interviews become less about capability and more about how well you can articulate in English. Even our entertainment reflects this divide - English-speaking protagonists are portrayed as sophisticated urbanites while Hindi or regional language speakers often become comic relief or village simpletons. What's most revealing is how we've normalized this linguistic apartheid - it's no longer the British imposing English upon us; we've become willing architects of our own cultural displacement. When a child in a Pune classroom is fined for speaking Marathi, or when a Chennai professional apologizes for their poor English despite being fluent in four Indian languages, we're not just speaking a language - we're reinforcing a hierarchy that continues to colonize our minds long after the colonizers have left.

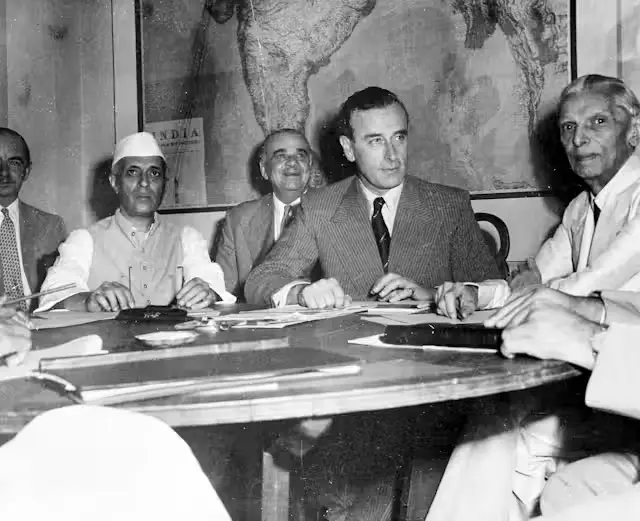

The masses follow what the elites do - it's a law of aspiration and human desire to be better and have better things. When I watch Bollywood's Kapoor family struggling to form basic Hindi sentences during their conference with Prime Minister Modi, I feel uneasy. The message the public receives is clear: Hindi? That sounds uncivilized - better to converse in English; that sounds so much sweeter.

Today, as I watch young Indians perfect their English pronunciation in coaching centers and parents stake out spots in admission queues, I see the completion of Macaulay's vision. We've internalized the colonial hierarchy so deeply that we perpetuate it ourselves. The question isn't whether English is useful in today's globalized world - it undeniably is. The question is where we lost our way in believing it's somehow superior to anything India could produce. I urge you to look at China, where every government document, research paper, and textbook is written in Chinese, not English. That surely doesn't stop them from dominating the tech field - which we Indians certainly like to brag we are good at.